The Paris Review With Ernest Heming Way Sumarry

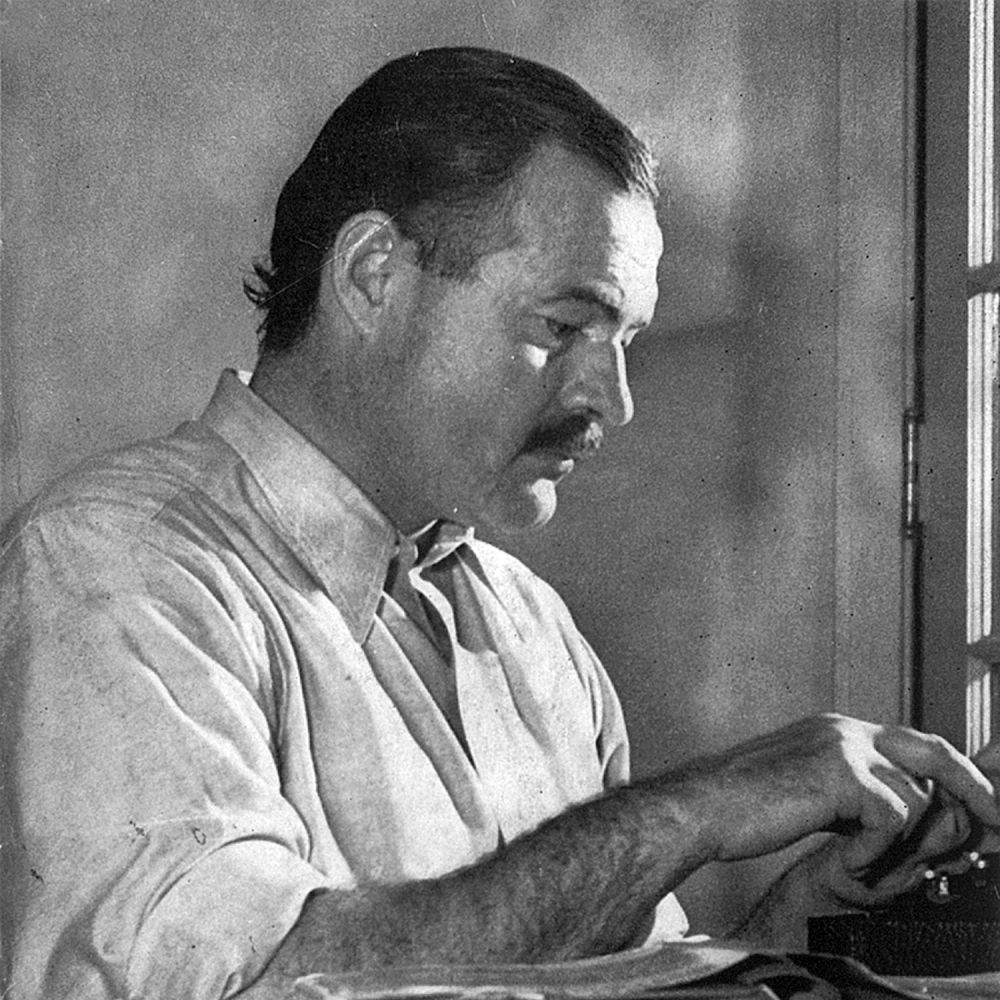

Ernest Hemingway, ca. 1939. Photograph by Lloyd Arnold

Ernest Hemingway, ca. 1939. Photograph by Lloyd Arnold

HEMINGWAY

Y'all go to the races?

INTERVIEWER

Aye, occasionally.

HEMINGWAY

Then you read the Racing Grade ... In that location you have the truthful art of fiction.

—Conversation in a Madrid cafe, May, 1954

Ernest Hemingway writes in the bedroom of his house in the Havana suburb of San Francisco de Paula. He has a special workroom prepared for him in a square tower at the southwest corner of the house, but prefers to piece of work in his bedchamber, climbing to the tower room only when "characters" drive him upwardly at that place.

The bedroom is on the ground flooring and connects with the chief room of the house. The door betwixt the 2 is kept ajar past a heavy volume list and describing "The Globe's Aircraft Engines." The bedroom is big, sunny, the windows facing e and southward letting in the solar day's low-cal on white walls and a yellow-tinged tile floor.

The room is divided into 2 alcoves past a pair of chest-high bookcases that stand out into the room at right angles from opposite walls. A large and low double-bed dominates one department, over-sized slippers and loafers neatly arranged at the pes, the 2 bedside tables at the caput piled seven-high with books. In the other apse stands a massive flat-pinnacle desk with two chairs at either side, its surface an ordered clutter of papers and mementos. Beyond it, at the far stop of the room, is an armoire with a leopard skin draped across the top. The other walls are lined with white-painted bookcases from which books overflow to the floor, and are piled on meridian amongst erstwhile newspapers, bullfight journals, and stacks of messages leap together by rubber bands.

It is on the elevation of one of these cluttered bookcases—the i against the wall past the east window and three feet or then from his bed—that Hemingway has his "piece of work-desk"—a foursquare foot of cramped area hemmed in past books on 1 side and on the other past a newspaper-covered heap of papers, manuscripts, and pamphlets. There is only enough space left on top of the bookcase for a typewriter, surmounted by a wooden reading-board, five or six pencils, and a chunk of copper ore to weight down papers when the wind blows in from the due east window.

A working habit he has had from the beginning, Hemingway stands when he writes. He stands in a pair of his oversized loafers on the worn pare of a lesser kudu—the typewriter and the reading-board chest-loftier contrary him.

When Hemingway starts on a project he always begins with a pencil, using the reading-board to write on onionskin typewriter newspaper. He keeps a sheaf of the blank paper on a clipboard to the left of the typewriter, extracting the paper a sheet at a time from under a metallic clip that reads "These Must Be Paid". He places the paper slantwise on the reading-board, leans against the lath with his left arm, steadying the paper with his hand, and fills the paper with handwriting which through the years has become larger, more boyish, with a paucity of punctuation, very few capitals, and often the flow marked with an 10. The page completed, he clips it facedown on some other clipboard which he places off to the right of the typewriter.

Hemingway shifts to the typewriter, lifting off the reading-lath, only when the writing is going fast and well, or when the writing is, for him at least, unproblematic: dialogue, for instance.

He keeps rails of his daily progress—"so as non to child myself"—on a large chart made out of the side of a paper-thin packing case and set up up against the wall nether the nose of a mounted gazelle head. The numbers on the chart showing the daily output of words differ from 450, 575, 462, 1250, to 512, the higher figures on days Hemingway puts in extra work so he won't experience guilty spending the following day fishing on the Gulf Stream.

A man of addiction, Hemingway does not use the perfectly suitable desk-bound in the other alcove. Though it allows more infinite for writing, it too has its miscellany: stacks of letters, a stuffed toy lion of the blazon sold in Broadway nighteries, a small-scale burlap bag full of carnivore teeth, shotgun shells, a shoehorn; woods carvings of lion, rhinoceros, ii zebras, and a wart-hog—these final set in a not bad row across the surface of the desk-bound—and, of class, books. You remember books of the room, piled on the desk, beside tables, jamming the shelves in indiscriminate club—novels, histories, collections of verse, drama, essays. A look at their titles shows their variety. On the shelf contrary Hemingway's human knee every bit he stands upwards to his "work-desk-bound" are Virginia Woolf'due southThe Mutual Reader, Ben Ames Williams'House Divided,The Partisan Reader, Charles A. Bristles'due southThe Commonwealth, Tarle'due southNapoleon's Invasion of Russian federation,How Young You lot Look by one Peggy Woods, Alden Brooks'sShakespeare and the Dyer'south Manus, Baldwin'sAfrican Hunting, T. S. Eliot'sCollected Poems, and 2 books on General Custer's fall at the battle of the Petty Large Horn.

The room, however, for all the disorder sensed at first sight, indicates on inspection an possessor who is basically dandy but cannot bear to throw anything away—especially if sentimental value is attached. One bookcase top has an odd assortment of mementos: a giraffe fabricated of wood beads, a little cast-iron turtle, tiny models of a locomotive, two jeeps and a Venetian gondola, a toy deport with a key in its dorsum, a monkey carrying a pair of cymbals, a miniature guitar, and a little tin model of a U.S. Navy biplane (one wheel missing) resting awry on a circular harbinger placemat—the quality of the drove that of the odds-and-ends which turn up in a shoebox at the back of a pocket-sized boy's closet. It is evident, though, that these tokens have their value, just equally three buffalo horns Hemingway keeps in his bedchamber have a value dependent not on size but because during the acquiring of them things went badly in the bush which ultimately turned out well. "It thanks me upwardly to wait at them," Hemingway says.

Hemingway may admit superstitions of this sort, but he prefers not to talk about them, feeling that whatever value they may take tin can exist talked away. He has much the same attitude near writing. Many times during the making of this interview he stressed that the arts and crafts of writing should not be tampered with by an excess of scrutiny—"that though there is one office of writing that is solid and you lot do it no harm by talking nigh it, the other is fragile, and if you talk well-nigh it, the structure cracks and you have nil."

Equally a event, though a wonderful raconteur, a man of rich humor, and possessed of an amazing fund of knowledge on subjects which involvement him, Hemingway finds it difficult to talk about writing—not because he has few ideas on the subject, but rather because he feels so strongly that such ideas should remain unexpressed, that to be asked questions on them "spooks" him (to employ one of his favorite expressions) to the bespeak where he is nearly inarticulate. Many of the replies in this interview he preferred to piece of work out on his reading-board. The occasional waspish tone of the answers is likewise function of this potent feeling that writing is a private, lonely occupation with no need for witnesses until the concluding work is washed.

This dedication to his art may suggest a personality at odds with the rambunctious, carefree, globe-wheeling Hemingway-at-play of popular formulation. The indicate is, though, that Hemingway, while plainly enjoying life, brings an equivalent dedication to everything he does—an outlook that is essentially serious, with a horror of the inaccurate, the fraudulent, the deceptive, the one-half-baked.

Nowhere is the dedication he gives his art more evident than in the xanthous-tiled sleeping room—where early in the morn Hemingway gets upwards to stand in accented concentration in front of his reading-board, moving but to shift weight from i pes to another, perspiring heavily when the work is going well, excited as a boy, fretful, miserable when the artistic touch momentarily vanishes—slave of a self-imposed discipline which lasts until about noon when he takes a knotted walking stick and leaves the business firm for the swimming pool where he takes his daily half-mile swim.

INTERVIEWER

Are these hours during the actual process of writing pleasurable?

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Very.

INTERVIEWER

Could y'all say something of this process? When exercise you work? Do you keep to a strict schedule?

HEMINGWAY

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning equally before long later first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is absurd or cold and you come to your work and warm as y'all write. You lot read what you have written and, every bit you always cease when yous know what is going to happen next, yous proceed from there. You write until yous come up to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you finish and try to live through until the side by side day when y'all striking it once more. You take started at half dozen in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you end you are as empty, and at the aforementioned fourth dimension never empty but filling, every bit when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing tin hurt you, nothing can happen, cypher means anything until the next twenty-four hour period when you exercise information technology over again. It is the wait until the next twenty-four hours that is hard to get through.

INTERVIEWER

Can you lot dismiss from your mind whatever projection you're on when yous're abroad from the typewriter?

HEMINGWAY

Of grade. But it takes discipline to practise it and this discipline is acquired. It has to be.

INTERVIEWER

Practice you lot do any rewriting as you read up to the place yous left off the twenty-four hours before? Or does that come later, when the whole is finished?

HEMINGWAY

I ever rewrite each twenty-four hours up to the point where I stopped. When it is all finished, naturally you go over information technology. You get another chance to correct and rewrite when someone else types it, and yous see it clean in type. The terminal chance is in the proofs. You're grateful for these different chances.

INTERVIEWER

How much rewriting practice you do?

HEMINGWAY

It depends. I rewrote the ending toGoodbye to Arms, the terminal page of it, thirty-ix times before I was satisfied.

INTERVIEWER

Was there some technical trouble there? What was it that had stumped you?

HEMINGWAY

Getting the words right.

corliswiliturkered.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4825/the-art-of-fiction-no-21-ernest-hemingway